|

||

|

What strikes observers of events in Italy is the difference between Italian political and cultural forces and those of the Western democracies. Very often, to justify this diversity, they point to an "Italian peculiarity" which is, however, never fully explained.

The left (and in particular the PDS, which succeeded the Italian Communist Party) is trapped in a corporative and statist culture which has no trust in the market economy and does not inspire confidence in prospective international partners. The moderate forces, mainly of Catholic inspiration, accept democratic political systems but remain fearful, in a confrontation with "open" societies, of losing their specific identity. And while the right appeals to Fascist nationalism, the Lega Nord upholds a brand of federalism which, beyond intentions, is more Yugoslavian than European or American. To create and develop a political class deeply rooted in liberal values, and thus in line with European models and open societies: this is the objective that the Radical leader Marco Pannella has been pursuing for over thirty years. This is the primary feature of the initiatives and the battles he has led, first in the "Italian" party and now in the "transnational and transdivisional" party. The campaign to permit divorce in Italy, begun in 1964 and concluded successfully in 1974, as well as upholding a fundamental civil right, initiated a more modern relationship between citizens and the state, a relationship that was more respectful of individual civil rights. As a young man Marco Pannella studied the writings of Benedetto Croce and Luigi Einaudi, as well as the Catholic Jacques Martitain, and was the pupil of the economist and politician Ernesto Rossi.

The first initiatives carried out by Marco Pannella and the young Radical Party (formed in the 1960s by a group of activists who funded all their own initiatives) were directed at the policies of Enrico Mattei and ENI, a state-run company. In his efforts to give Italy an independent source of energy through ENI, Enrico Mattei (and later his successor Eugenio Cefis) adopted a practice of political corruption, without distinction between government and opposition parties, in order to avoid being under their control and to assure their support in parliament, where funds and orders were allocated. The practice became widespread: all the large state companies, IRI just as much as ENI, learnt to ask for economic aid and support from the government through the unanimous votes, in parliament, of all the parties. In this way, an enormous sector of the Italian economy (from industry to banking) came to be conditioned by blackmail from the parties, who began to take control and appoint their own men to management positions, receiving vast illegal funds without regard for the needs of efficient industrial and economic management. The widespread, uncontrollable interference of the parties led to the decline of the public (and also the private) economic and industrial system, and is at the root of the political corruption finally brought to light by the magistrate Di Pietro and his colleagues. It was not only in the economy, however, that Pannella and the Radicals, from the 1960s onwards, felt the need to fight the risks caused by the lack of a clear distinction between government and opposition roles that characterized Italian politics: the risks, that is, of the spread of the arrogant despotism of the parties, which had penetrated deep into the structures of the state, for the rights of the citizen and the institutions of government and state. The Radicals therefore followed with great attention the civil rights movements which were gaining ground in the United States and the Anglo-Saxon world; in those movements they saw a possible model, a way of conceiving politics - on the basis of pragmatic rather than ideological issues, supported by the free consensus of organized and self-funding groups of citizens - which could be tried in Italy as a remedy to the increasingly undemocratic party system.

Elected to parliament for the first time in 1976, Marco Pannella directed his parliamentary campaigns against parliamentary rules and procedures which distorted the roles and the responsibilities of both government parties and the opposition. Most laws were passed in commissions, by unanimous vote or by majorities that Pannella often described as "Bulgarian". Even the Communist Party, in fact, took part in this share-out. During the period of stagnancy caused by the Cold War, the Communist Party, which was formally in opposition, was in reality given a substantially governmental role; this allowed it to prevent the country from evolving towards Western or liberal models. The effects of this widespread parliamentary practice were felt both at economic level (as we have seen) and at the level of civil rights. Aberrant laws and provisions

were introduced, to the extent that Italy was brought before the Court

of Justice in the Hague (after the introduction of the principle that

the "preventive imprisonment" Almost alone, Marco Pannella and the Radical deputies fought this scandalous development and the illegal practices, using all the classic instruments of Western parliamentary politics, at times turning to difficult forms of obstructionism. This intransigent opposition was, as we would expect, fought off in every possible way: first of all by preventing the country from knowing about it. The task of silencing Pannella's battle was entrusted above all to the state TV network, which stuck closely to the orders of the parties in power (at the time the state TV network had a monopoly on news programmes).

Since 1976, Pannella has continued to retain his seat in the Chamber of Deputies. Similarly, he has held his seat as a member of the European Parliament since 1979. Precisely because of his European and international experience, he was able to tackle a problem that was shortly to explode in dramatic forms: that is, the famine that caused millions of victims in the Third and Fourth Worlds. Pannella denounced the true

causes of this tragedy, that is the lack of interest on the part of

the rich countries and mistaken policies (in the demographic field,

for example), rather than the "natural" causes which had so

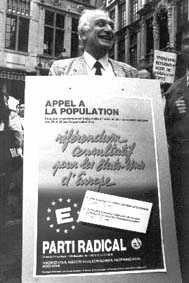

far been called on as a justification and an alibi. The problem was all the more serious in the light of the fact that, in the general silence and inertia, the USSR and its satellites were beginning a process of penetration, especially in Africa, that threatened to have extremely serious consequences. With the outbreak of the moral and political crisis in Italy, between 1991 and 1993, Marco Pannella reaped the fruits of his campaigns against the excessive power of the old, corrupt parties. For some time he had been proposing the Anglo-Saxon electoral system (first-past-the-post, with the necessary adjustments), the only model which in the 1930s had stood up to Communist and Fascist totalitarianism, and which is able to ensure political and governmental stability. None of the Italian parties wanted this reform, yet in 1992, albeit in a distorted and inadequate form, an embryonic first-past-the-post system was introduced both for general and local elections. In the Parliament elected

in 1992, Pannella assumed an important role by supporting the candidacy

of Oscar Luigi Scalfaro as President of the Republic, and by taking

up the leadership of the forces that are working for a smooth transition

towards new political forms and structures, looking ahead to modern,

liberal, and Western models of parliament and government, solidly based

on both the market and the defence of the international institutions,

the EU and the UN. During the same period, having exhausted its task, the Radical Party which he had led since the 1960s was refounded as the transnational and transdivisional Radical Party, completely renewing its executive and its composition and beginning to operate in a scenario that is no longer limited to Italy.

|

|

This peculiarity, which makes it difficult

for Italy to join the ranks of the liberal-democratic countries, is

in actual fact due to the absence, or at least the weakness, of political

leadership based on a solid liberal tradition.

This peculiarity, which makes it difficult

for Italy to join the ranks of the liberal-democratic countries, is

in actual fact due to the absence, or at least the weakness, of political

leadership based on a solid liberal tradition.  Rossi fought a solitary campaign to

dismantle the statist, corporative, trade unionist economy, inherited

from the Fascist period but continued after the war by large sectors

of the Catholic world in government, and also by the left and the Communist

Party in opposition.

Rossi fought a solitary campaign to

dismantle the statist, corporative, trade unionist economy, inherited

from the Fascist period but continued after the war by large sectors

of the Catholic world in government, and also by the left and the Communist

Party in opposition.  Equally, the choice of the Gandhian

model of nonviolence expressed a profound belief in the values of tolerance

and dialogue, without which even formal democracies are unable to ensure

justice and liberty.

Equally, the choice of the Gandhian

model of nonviolence expressed a profound belief in the values of tolerance

and dialogue, without which even formal democracies are unable to ensure

justice and liberty.  of alleged offenders could be extended,

without trial, for up to twelve years).

of alleged offenders could be extended,

without trial, for up to twelve years).  For a long time this silence, and the

defamatory campaigns to which they were subject, prevented the Radicals

from growing and increasing consensus: and yet in the 1979 elections

they managed a total of 20 deputies and senators.

For a long time this silence, and the

defamatory campaigns to which they were subject, prevented the Radicals

from growing and increasing consensus: and yet in the 1979 elections

they managed a total of 20 deputies and senators.